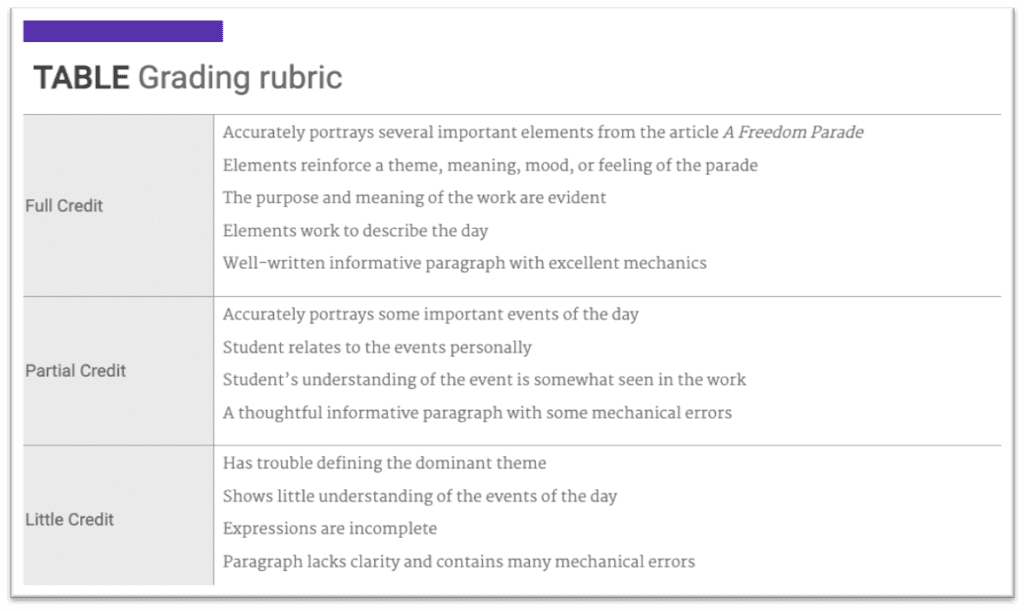

Activity: Freedom Parade Collage

February 17, 2021

The following activity has been extracted from our African American History course / Unit 4: African Americans and the Civil War.

Directions:

- Read the news article then complete the following activity. Use the rubric located below the activity to assess how you are completing each of the required components.

- (Optional): For teachers and parents looking to use it as a graded activity, a rubric is located at the bottom of the activity.

News Article

Stories They Tell: A Freedom Parade

In Charleston, South Carolina, black people held a parade as thousands of marchers expressed their joy, hope, and sheer excitement at being free. Like their white counterparts, African Americans symbolized deeply held beliefs and feelings in banners, songs, and dramatic tableaux.

From the New-York Daily Tribune, April 4, 1865:

Charleston, March 27, 1865

There was the greatest procession of loyalists in Charleston last Tuesday that the city has witnessed for many a long year. The present generation has never seen its like. For these loyalists were true to the Nation without any qualifications of State rights, reserved sovereignties, or other allegiances; they gloried in the flag, they adored the Nation, they believed with the fullest faith in the ideas which our banner symbols and the country avows its own. It was a procession of colored men, women and children, a celebration of their deliverance from bondage and ostracism; a jubilee of freedom, a hosannah to their deliverers.

The celebration was projected and conducted by colored men. It met on the Citadel green at noon. Upward of ten thousand persons were present, colored men, women and children, and every window and balustrade overlooking the square was crowded with spectators. This immense gathering had been convened in 24 hours, for permission to form the procession was given only on Sunday night, and none of the preliminary arrangements were completed till Monday at noon.

Gen. Hatch, Admiral Dahlgren and Col. Woodruff gave their aid to the movement; and thereby the 21st Regiment of U.S.C.T., a hundred colored marines and a number of national flags gave dignity and added attractions to the procession.

The procession began to move at one o’clock under the charge of a committee and marshalls on horseback, who were decorated with red, white and blue sashes and rosettes.

First came the marshals and their aid[e]s, followed by a band of music; then the 21st Regiment in full form; then the clergymen of the different churches, carrying open Bibles; then an open car, drawn by four white horses, and tastefully adorned with National flags. In this car there were 15 colored ladies dressed in white, to represent the 15 recent Slave States. Each of them had a beautiful bouquet to present to Gen. Saxton after the speech which he was expected to deliver. A long procession of women followed the car. Then followed the children of the Public Schools, or part of them; and there were 1,800 in line, at least. They sang during the entire length of the march:

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

His soul is marching on!

Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

We go marching on! . . .

Very few of these children had ever been at school before; not one of them had ever walked in a public procession; they had had only one hour’s drill on their playground; and yet they kept in line, closed up, and were under perfect control and orderly up to the last. They only ceased to sing in order that they might cheer Gen. Saxton, Col. Woodford, various groups of Union officers or sailors, or one or two Northern men whom they recognized as their friends. Gen. Saxton and lady were in a carriage at one street where the procession passed, and Col. Woodford and lady at another; and one continuous cheer greeted them, mingled with cheers for an officer whom they supposed to be Gen. Hatch. The colored people know all these officers as their friends. Gen. Saxton is their favorite everywhere in the Department, and they have all learned that Gen. Hatch and Col. Woodford gave them equal rights in the public schools, an advantage which they prize next to freedom. . . .

The most original feature of the procession was a large cart, drawn by two dilapidated horses with the worst harness that could be got to hold out, which followed the trades. On this cart there was an auctioneer’s block, and a black man, with a bell, represented a negro trader, a red flag waving over his head; recalling the days so near and yet so far off, when human beings were made merchandise of in South Carolina. This man had himself been bought and sold several times and two women and a child who sat on the block had also been knocked down at public auction in Charleston. . . .

. . . Old women burst into tears as they saw this tableau, and forgetting that it was a mimic scene, shouted wildly, Give me back my children! Give me back my children! The wringing of hands seen on the sidewalks caused more than one looker-on to curse the policy that would even suggest the possibility that the wretches who had bought and sold loyal men might be or ought to be readmitted to the rights of citizenship. . . .

Behind the auction-car 60 men marched, tied to a rope, in imitation of the gangs who used often to be led through these streets on their way from Virginia to the sugar-fields of Louisiana. All of these men had been sold in the old times. . . .

Then came the hearse, a comic [feature] which attracted great attention, and was received with shouts of laughter. There was written on it with chalk.

“Slavery is Dead.”

“Who Owns Him?”

“No One.”

“Sumter Dug His Grave on the 13th of April, 1861.”

. . .

The great procession took one hour and twenty minutes to pass any point. On the return to the citadel where a stand was prepared for Gen. Saxton and the other speakers, there were at least 10,000 persons assembled. There were 4,200 men in the procession by count, exclusive of the military, the women and the children.

A shower of rain, which began to fall as the procession arrived at the citadel, rendered it expedient to postpone a speech.

Rev. Mr. French led in singing a doxology, and the great assembly dispersed in an orderly manner after enthusiastic and prolonged cheers for Gen. Saxton, the Yankees, the Star Spangled Banner, and a final, tumultuous and long continued three times three for Abraham Lincoln.

The fears so lately expressed that an outpouring of the colored people would produce a riot is thus shown to be unfounded. “Fear the slave who breaks his chain, free the slave and fears are vain,” is a truth which these modern Rip Van Winkles who take the oath here and think that they are Union men do not yet begin to suspect, far less to believe.

ACTIVITY

Freedom Parade Collage

Create a collage that depicts the Freedom Parade in 1865. Your collage should tell the story, including the look, purpose, and historical significance of this event.

- Use clipart and a word processor, or a graphics program, to create your collage. You might also want to use a paper form like magazines and/or newspapers; a hand drawing is also acceptable.

- Submit your collage with a paragraph or two describing the presentation. Include information on why the selected elements (tableaux, banners, songs) were important for this historic event. Do you agree that the events of the day give a glimpse into what freedom meant to the African-American people of South Carolina in 1865?